Matias del Campo is an architect, designer, and theorist specializing in the intersection of artificial intelligence and architecture. He is the Director of the ARIL Laboratory for Architecture and Artificial Intelligence at the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) and an Associate Professor of Architecture at the institution.

In 2003, he co-founded SPAN in Vienna with Sandra Manninger, establishing a practice renowned for integrating advanced computational methodologies with architectural design and philosophical inquiry—a framework they define as a design ecology. His work has been recognized with prestigious accolades, including the Accelerate@CERN fellowship and the AIA Studio Prize.

Del Campo serves on the Board of Directors for the Association for Computer-Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA), actively contributing to the discourse on architectural computation. His work is featured in esteemed collections such as FRAC, the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna, the Benetton Collection, and the Albertina.

A prolific author, he has published extensively on the convergence of AI and architecture, with notable works including Neural Architecture, Diffusions, Machine Hallucinations, and Artificial Intelligence and Architecture. Through both his research and practice, Del Campo continues to shape the evolving dialogue between emerging technologies and architectural innovation.

The Evolution of AI in Architecture.

Matias del Campo, a leading voice in artificial intelligence and architecture, has authored several books on AI-driven design, including Neural Architecture: Design and Artificial Intelligence, Diffusions in Architecture—which explores image generators and their impact on architectural design—and two editions of Architectural Design (AD) dedicated to AI: Hallucinating Machines and Architecture and Artificial Intelligence. His latest publication on the subject was released just a few months ago.

Now, as I work on an AI research sponsored by HP and NVIDIA, it is both an honour and an exciting opportunity to sit down with him and discuss his journey, the impact of AI in architecture, and what the future holds for the industry.

His journey into AI and architecture began in the late 1990s, in what he humorously refers to as "the Stone Age" of computational design. Alongside his partner, Sandra Manninger, del Campo had early exposure to AI research through connections at the Austrian Institute of Artificial Intelligence in OFAI. At the time, AI was in its infancy—far from the sophisticated neural networks we have today. Their initial discussions with AI researchers were speculative, as even basic neuron-to-neuron interactions were difficult to simulate.

"If you think about it, every pixel in a generated image can be considered a neuron," del Campo explains. "So, to get anything meaningful out of these machines, you need a vast number of them."

Over the years, as AI technology advanced, del Campo recognized its growing potential in architectural design. A pivotal moment came after his work on the Austrian Pavilion for the Shanghai Expo 2010. By 2013-14, generative adversarial networks (GANs) had emerged, marking a technological shift that made AI-generated design viable. "That’s when I realized—we’re there now," he recalls.

This realization coincided with his appointment at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. There, he met Jessy Grizzle, the director of robotics, and together they explored research opportunities in AI and design. Del Campo was particularly keen on leveraging AI as a design tool, which led to a collaboration with Robotics PhD student Alexandra Carlson.

The result was the establishment of the Laboratory for Architecture and Artificial Intelligence. This initiative fostered interdisciplinary exchange, with graduate students from computer science working alongside architecture students. "They would come to our studio and teach students how AI algorithms work, how neural networks function, how to program them, build datasets, and optimize predictions," del Campo explains.

The lab’s success led to the development of a dedicated GitHub repository and the university's investment in cloud computing resources, enabling students to train their own AI models. This pioneering work took place between 2017 and 2022—before the explosion of tools like Midjourney, DALL·E, and ChatGPT.

"The students at Taubman College were incredibly brave," del Campo notes. "I was offering them a new and uncharted area of research, but they embraced it fully."

Alongside collaborators Alexandra Carlson and Danish Syed, Matias del Campo became a prolific researcher in the field of AI-driven architecture, producing numerous conference papers that explored its theoretical and practical implications. These early investigations laid the foundation for his books, which sought to bridge the emerging world of AI technologies with the discipline of architectural theory.

"I kept waiting for a young theorist to step up and tackle this subject, but no one was doing it," del Campo recalls. "At some point, I realized—if no one else is writing about it, I will."

His books engage with pressing questions that challenge long-held assumptions about architectural creativity and authorship:

What does it mean for architects to collaborate with learning machines? Should we resist AI, embrace it, or simply treat it as another tool in our design arsenal? These reflections materialized in Neural Architecture, published in March 2022—just as AI-powered design tools like MidJourney were still in beta testing.

House of Feathers; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

Long before the mainstream design community recognized its potential, del Campo had already begun experimenting with AI-generated imagery. One of his earliest creations—a conceptual house composed of feathers—was posted on Instagram, catching the attention of his friend, designer Kory Bieg. "Matias is onto something," he remarked. It was a turning point that signaled the growing visibility of AI-generated architecture, fueling a rapid expansion of interest in the field.

Yet, despite this explosion of AI in architecture, many in the profession have struggled to keep pace with its implications. "Even in my interviews with leading firms—I sensed hesitation. Most were still engaging with AI in purely moral terms, uncertain of how to practically implement it into their design processes." I noted.

Del Campo understands these apprehensions firsthand, particularly from the next generation of architects. "When new students enter my studio, their first question is almost always, ‘Will I even have a job when I graduate?’ They see AI as a looming threat," he explains. "But by the end of the semester, that fear disappears. They realize AI isn’t here to replace them—it’s a tool they can leverage to enhance their work."

Rather than framing AI as an existential crisis for architects, del Campo urges the profession to recognize its dual nature—a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde paradigm, as he describes it.

"Mr. Hyde represents the artistic, cultural, and philosophical side of AI—the speculative, expressive, and critical aspects. That’s what people see in books, in social media, in magazines," he explains.

"But then there’s Dr. Jekyll—the more pragmatic, research-driven side. This is where AI is used for optimisation, predictive modelling, and solving real-world design challenges. It’s about improving structural efficiency, minimising material waste, extending the lifecycle of buildings, and even addressing issues of repurposing and demolition debris."

At the University of Michigan, del Campo’s lab was at the forefront of such research, pioneering methodologies that blend AI with practical applications in architecture and construction. His commitment to this work remains steadfast, as he continues to push the boundaries of what AI can offer to the profession.

For del Campo, the path forward is clear: "We have to move beyond fear and toward strategic integration. AI is not here to replace architects—it’s here to expand what we can do."

AI as a Tool for Architectural Innovation: The Robot Garden and Beyond

While much of Matias del Campo’s AI-driven research delves into abstract and theoretical aspects, his projects also engage with tangible architectural problems. Some of his most intriguing work lies in pragmatic, data-driven explorations—those that may not produce the most visually captivating imagery but significantly impact the way architects approach design, optimization, and material efficiency.

Del Campo’s research extends beyond purely aesthetic experiments; many of his AI-generated concepts have been rigorously tested through small-scale prototypes, serving as experimental test beds for future architectural applications. Among these, the Robot Garden and Dog House stand out as pivotal projects that demonstrate AI’s role in augmenting, rather than replacing, traditional architectural methods.

Robot Garden; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

Dog House; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

Dog House; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

“I recently gave a lecture where I outlined exactly how AI can be applied at every stage of architectural design,” del Campo explains. “For example, with Robot Garden, we ran a rapid series of design iterations long before tools like MidJourney existed. Instead of using

off-the-shelf AI generators, we trained our own Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) from scratch. We built a custom dataset that included fountains, gardens, terrains, satellite imagery, and architectural columns—essentially teaching the AI to recognize certain spatial and formal characteristics before generating entirely new ones.”

This bespoke approach to AI training was still highly experimental in 2019, when the Robot Garden was designed. At the time, image generators were still rudimentary, and AI’s role in architecture was largely unexplored. Unlike today’s automated tools, del Campo and his team worked closely with computer scientists who wrote the code, trained the models, and ran the algorithms for days to generate thousands of images.

“No architect can do 3,000 sketches in a single day,” del Campo notes. “AI allowed us to explore an expansive range of possibilities at an unprecedented speed. But, of course, the human component remained crucial. We still had to curate and select the best results from these thousands of options. That’s where architectural intuition comes into play.”

The next challenge was translating these AI-generated 2D images into 3D architectural models—an issue that remains central to AI-driven design today. “Back then, we were experimenting with very early-stage 2D-to-3D transformations,” he recalls. “The Robot Garden was designed right before the COVID-19 pandemic, around February or March 2019, using what would now be considered primitive techniques. Still, it was a groundbreaking attempt at bridging AI-generated imagery with architectural form.”

Similarly, the Dog House project sought to answer a fundamental question: How can AI-generated 2D imagery be directly transformed into buildable three-dimensional architecture? The process involved taking images produced in MidJourney and using them to generate sectional drawings, which were then projected into 3D models. “It was a very direct translation,” del Campo explains. “We literally extracted AI-generated sections and used them to construct a three-dimensional object.”

Beyond AI Tools: Customizing Code for Architecture

While many architects today rely on commercial AI tools, del Campo has always advocated for a deeper level of engagement—one that involves customizing, adapting, and even creating new AI models tailored to specific architectural problems.

“These aren’t just software programs you can buy off the shelf,” he explains. “What we do is take existing code—for example, a generative adversarial network script—and modify it to fit our needs. We don’t just use a pre-made AI model; we adapt the datasets, optimize certain parameters, and train it to respond to architectural challenges. That’s the level of customization we need in architecture.”

This approach contrasts with the industry’s reliance on closed-system software tools, which del Campo believes are increasingly outdated. “The idea of pre-packaged, one-size-fits-all architectural software is coming to an end,” he asserts. “Every project presents unique challenges, and architects need to find bespoke solutions. That means engaging with AI not just as a consumer, but as an active participant in shaping the technology.”

However, del Campo is quick to clarify that architects don’t need to become expert coders themselves. “It’s just like structural engineering,” he says. “As architects, we study structural principles, but we don’t become structural engineers. We learn enough to communicate effectively with them. The same should apply to AI and coding—architects should understand the fundamentals, but they don’t have to be the ones writing the algorithms. That’s what collaborations with computer scientists are for.”

This interdisciplinary approach—where architects guide AI-driven processes rather than simply consuming them—represents a fundamental shift in design methodology. Del Campo’s work, from Robot Garden to Dog House, exemplifies how AI can be leveraged as a tool for architectural experimentation, optimization, and creative exploration. Rather than replacing architects, AI expands the boundaries of what’s possible, accelerating innovation while keeping the human touch at the center of the design process.

For del Campo, the message is clear: AI isn’t here to replace architecture—it’s here to redefine it.

Rethinking Architectural Design: AI, Estrangement, and the Future of Innovation

One of the most unexpected challenges Matias del Campo encountered in integrating AI into architectural workflows was learning to relinquish control. Architecture, traditionally a top-down process, had always been about a designer’s vision—an idea conceived in the mind, sketched on paper, and translated into digital form. But working with AI fundamentally disrupted that paradigm.

“I had to completely rethink my approach to architecture,” del Campo explains. “Previously, I would envision a design and execute it step by step. But AI introduced a new, emergent process—one where the machine learns from vast datasets, identifies patterns, and generates thousands of possible solutions. Instead of controlling every aspect, I had to allow the process to unfold and curate the best outcomes.”

This shift was transformative. It led del Campo to reconsider the nature of architectural creativity itself. “For the first time, I saw creativity not as something purely human, but as a multi-agent system. It’s no longer just the architect—it’s humans, machines, landscapes, biology, and geology, all contributing to the design process. No single person can process that much data alone. We need machines to do that. And instead of resisting it, we should embrace the immense potential it brings.”

That moment—when he let go of absolute control—was profoundly liberating. “It was a realization that architecture is no longer about imposing a singular vision. It’s about collaborating with intelligence beyond our own and allowing the unexpected to emerge.”

The Balance Between Familiar and Alien in AI-Generated Architecture

One of the most compelling aspects of AI-generated design is its ability to occupy a space between the familiar and the alien. This tension, del Campo argues, is key to producing work that is both innovative and functional.

“One of the first things I realized is that AI, by its nature, doesn’t truly invent anything new,” he explains. “It works entirely with existing data—it can only interpolate between existing data points from what already exists. That’s why AI-generated designs often feel strangely familiar. They aren’t radically new—they are recombinations of the known.”

This phenomenon, however, has both strengths and limitations. “The early days of AI-generated design were exciting because the results were unpredictable and strange. But as AI has improved, its outputs have become more polished—too perfect, even. MidJourney, for example, has become somewhat boring. It generates beautiful images, but there’s little surprise left. The more strange and unfamiliar something is, the more interesting it becomes to me.”

Del Campo draws on artistic and psychological theories to explain why strangeness is so compelling. “Think about Viktor Shklovsky’s theory of estrangement in the arts or Sigmund Freud’s concept of the uncanny. Our brains are wired to recognize the familiar, but when something contains both the recognizable and the unfamiliar, it forces us to pay closer attention.”

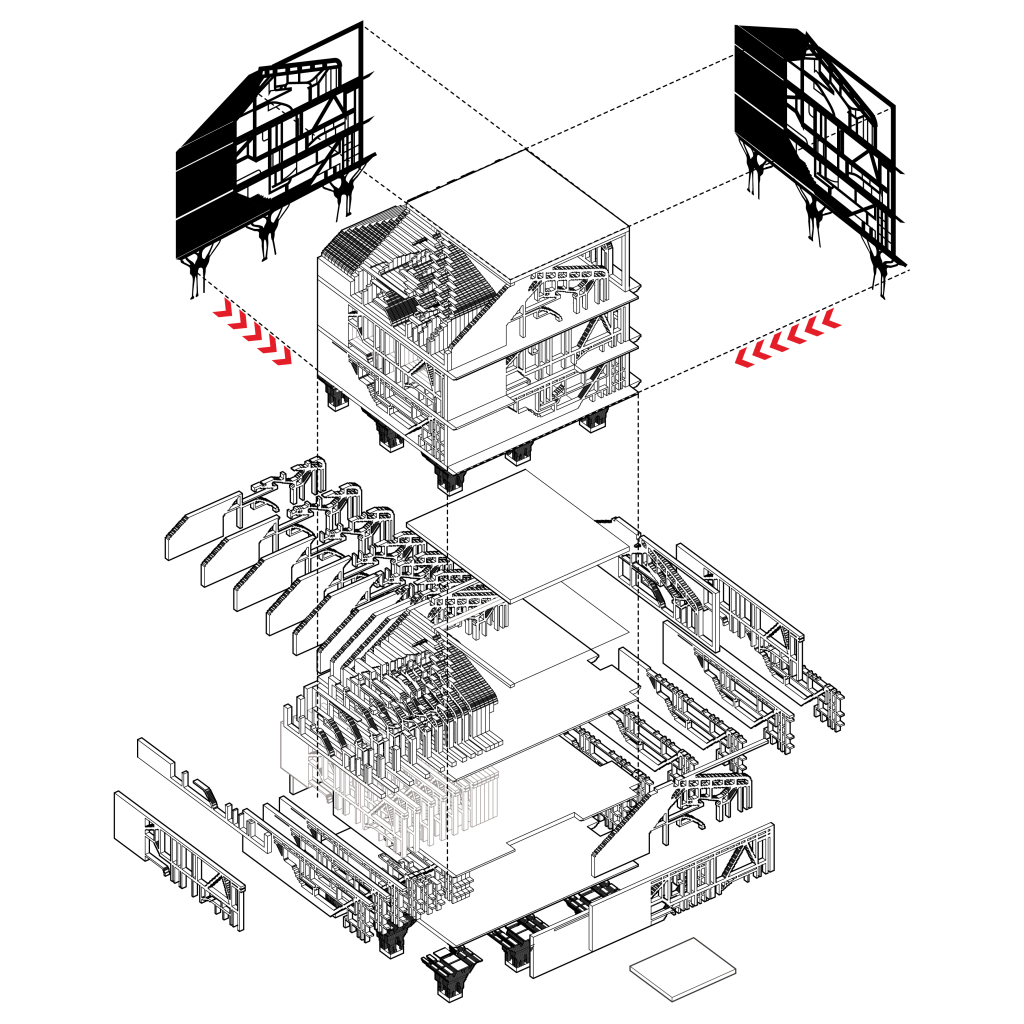

Alpina Villa; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

In architecture, this principle can be a powerful design tool. “There’s an image I often show in lectures—a building standing on a mountain. A trained architect immediately recognizes familiar modernist features: cantilevers, concrete elements, aluminum mullions, long window bands. But then something feels off. The way the building meets the ground is ambiguous. Was it carved from the rock? Is it growing out of the earth? Was it damaged? That sense of disorientation makes us stop and think. It forces us to question what we see.”

This balance between recognition and estrangement, del Campo argues, is what makes AI-driven architecture so compelling. “It allows us to create spaces that are grounded in architectural language yet feel new and unexpected. It pushes the discipline forward.”

Moving Beyond the Architectural Status Quo

For del Campo, much of what is considered “advanced” architecture today is, in fact, outdated. “Many people still associate contemporary architecture with curvilinear, parametric forms. But parametricism isn’t new—it dates back to the 1990s. What people see as ‘cutting-edge’ is really just a continuation of ideas that were already well-established last century.”

He compares this stagnation to the early 20th century. “Imagine it’s 1924, and you have radical thinkers like the modernists pushing architecture forward. But the mainstream still believes Art Nouveau is the pinnacle of design. That’s exactly where we are today. People still think these fluid, algorithmic forms are the future, when in reality, they are relics of the past.”

For architecture to truly progress, del Campo believes it must embrace AI as more than just a generative tool—it must integrate AI’s potential into the very logic of architectural design, from concept to construction. “We need to stop treating AI as a gimmick for making pretty images and start seeing it as a way to fundamentally rethink how we design, build, and interact with space. That is where the real revolution lies.”

AI, he insists, is not here to replace architecture—it’s here to redefine it.

The Future of AI in Architecture: A Profession Transformed but Not Replaced

As AI continues to integrate into architectural workflows, its long-term impact on the profession remains a topic of both excitement and uncertainty. Looking ahead, Matias del Campo envisions a dramatic shift in how architects work, but not in the way many fear.

Diagram: AI Impact; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

“There was an interesting diagram published by a major economics magazine—it showed the percentage of job sectors that will be affected by AI in the next decade,” del Campo recalls. “Architecture was ranked as the third most impacted field, with 37% of jobs expected to change. That’s almost every third job in architecture.”

However, he is quick to clarify: “It doesn’t mean those jobs will disappear—it means they will change. The way we design, the way we communicate with clients, the way we generate and optimize projects will be fundamentally different.”

And that shift is already happening. “I have students today using large language models to generate 3D models in Rhino,” he explains. “They simply describe the shape or parameters they want, and AI generates the Python code to create those forms inside the software. It’s only a matter of time before we can verbally describe an entire architectural concept and have AI instantly generate it in a 3D modeling environment.”

This transition represents a fundamental shift away from traditional, visually driven design processes. “Right now, we think of architecture as something highly visual—sketching, modeling, rendering. But AI introduces the possibility of designing with language. Imagine describing a spatial experience instead of drawing it. That’s an entirely new way of thinking about architecture.”

Optimization and Prediction: AI’s Greatest Strengths

Beyond generative design, del Campo believes AI will revolutionize architecture in two key ways: optimization and prediction.

“The concept of optimization in architecture is undergoing a semantic shift,” he says. “Traditionally, we think of optimization in engineering terms—structural efficiency, material reduction, sustainability. AI enhances these aspects, making buildings more resilient, resource-efficient, and better suited for specific environmental conditions.”

But AI-driven optimization isn’t limited to technical performance. “We can also optimize for human experience, imagination, and contextual harmony. If I’m designing a building in an existing urban fabric, AI can analyze the surrounding environment and suggest solutions that either blend in seamlessly or create a new landmark presence. These are architectural decisions, not just engineering ones.”

Prediction, on the other hand, opens up even greater possibilities. “Imagine two cities planning to merge into a single metropolitan area. AI can model how the growth will unfold, where infrastructure should be placed, how to create a walkable 15-minute city, and what resources will be needed to support the population. We can simulate urban development before it happens.”

The implications extend to small-scale projects as well. “You could sketch a simple living room, indicate north and south orientations, and let AI predict the optimal layout for bedrooms, bathrooms, and circulation paths based on sunlight, privacy, and functional needs. We’re already seeing early versions of these tools in practice.”

At the Association for Computer-Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA) conference, del Campo witnessed how quickly these innovations are evolving. “Two years ago, my students were using ChatGPT to generate point coordinates for Rhino. This year, people are already developing fully functional tools that integrate large language models directly into architectural design workflows. The pace of advancement is astonishing.”

Will AI Replace Architects?

Despite these rapid developments, del Campo is not concerned about AI making architects obsolete. In fact, he sees the role of the architect becoming more essential than ever.

“There’s always this fear—if AI can generate 5,000 different design options for a house, will architects still be needed? The answer is yes, absolutely,” he asserts. “Because architecture is not just about generating forms—it’s about understanding people.”

One of the most overlooked aspects of an architect’s role is their ability to educate and guide clients. “We don’t just design buildings; we teach our clients about aesthetics, style, and lifestyle. An AI-generated design might give them 5,000 options, but without architectural knowledge, they might pick the worst one.”

Architects, he argues, provide curation and expertise—the ability to recognize not just what can be built, but what should be built. “I can tell a client, ‘Yes, this design is technically possible, but you won’t feel comfortable living in it for these reasons.’ AI lacks that level of human intuition.”

More importantly, architecture is a deeply personal, human-centric profession. “A machine can analyze a questionnaire, but it can’t have a drink with your client, listen to their unspoken concerns, and intuitively understand their aspirations. That human factor is irreplaceable.”

As AI becomes more embedded in the architectural process, del Campo believes architects will need to focus more on empathy, creativity, and critical thinking. “The future of architecture isn’t about competing with AI—it’s about collaborating with it. The architects who will thrive are those who learn how to integrate AI into their workflow while maintaining the irreplaceable human elements of design.”

For del Campo, the future is not a battle between architects and machines—it’s an evolution of the profession itself. “AI isn’t here to take over architecture,” he says. “It’s here to make architects even more powerful.”

AI as a Competitive Advantage for Architecture Firms

The integration of AI into architecture is not just about efficiency—it’s also about competition. For Matias del Campo, technology has always been a means of gaining an edge in the industry.

“One of the reasons I was always drawn to technology was its potential to level the playing field,” he explains. “I realized that if I could master certain software tools, I could design faster than large firms. That meant I could participate in more competitions, stay agile, and remain competitive even as a small practice.”

AI offers similar advantages, allowing firms—large and small—to rethink how they approach projects. But del Campo sees two distinct outcomes emerging from this technological shift.

“Big architecture firms are going to become even bigger,” he predicts. “They’ll be able to produce work faster, ensure consistency, and maintain quality control through automation. They can also afford to build their own proprietary AI tools—running their own servers, training custom models, and investing in expensive GPUs to optimize workflows. That kind of infrastructure is simply out of reach for smaller firms.”

At the other end of the spectrum, del Campo envisions a resurgence of boutique architecture studios specializing in handcrafted, deeply personalized design. “When everything becomes automated, the handcrafted, human-made aspect of architecture will become a luxury,” he explains. “Think about watches—you can buy a $20 digital watch that keeps time perfectly, or you can buy a $50,000 Swiss watch as a status symbol. In the same way, architecture will bifurcate into mass-produced, AI-driven design and high-end, bespoke projects that are valued precisely because they weren’t created by machines.”

However, del Campo acknowledges that for small firms to successfully position themselves as luxury brands, they must embrace marketing and branding—skills that many architects lack.

“As an industry, we don’t communicate well,” he says. “Many firms struggle to articulate their unique value proposition. If an architecture office specializes in hand-drawn, one-of-a-kind designs, they need to brand themselves accordingly—make it clear that what they’re offering is special.”

I agree with Mattias, the industry has historically been slow to adopt marketing strategies.

“For decades, architecture firms weren’t even allowed to advertise. That’s part of why architects have never fully developed these skills. But branding, storytelling, and clear communication are crucial for positioning yourself in the market—whether you’re leveraging AI or resisting it.”

AI and Multidisciplinary Collaboration in AEC

AI is also poised to transform collaboration within the AEC industry, helping architects, engineers, and contractors streamline workflows and improve communication. One of the biggest inefficiencies in the industry today is the disconnect between different disciplines—something del Campo believes AI can help resolve.

“We already have a tool that helps with this tremendously: parametric modeling,” he points out. “If you do it correctly, everyone—architects, engineers, even clients—can work from a single model in the cloud. This eliminates the issue of multiple, disconnected models floating between different offices. Everyone is working with the same dataset in real time.”

The problem, he argues, is that the industry isn’t using this tool to its full potential. “Parametric modeling has been around for over 20 years, but it still hasn’t been fully embraced. If firms took it more seriously, we’d already have far better interdisciplinary collaboration.”

Bridging the Gap Between Design and Construction

Another major area where AI can drive innovation is in closing the gap between conceptual design and construction. One of the most promising technologies for achieving this, according to del Campo, is augmented reality (AR).

“If I train a neural network to recognize construction errors, I can have someone walk through a construction site wearing AR glasses,” he explains. “The AI can instantly compare what’s being built to the digital model, highlighting mistakes in real time. If a wall is slightly out of alignment or a beam is installed incorrectly, the AR glasses will flag it before it becomes a costly problem.”

This technology can also be used proactively, ensuring precision before errors occur. “Instead of waiting for mistakes to be caught later in the process, AI can continuously scan the site, compare the physical structure to the planned design, and warn workers if something isn’t matching up. It’s an entirely new level of quality control.”

AI-powered machine vision is another game-changer. “Machine vision allows AI to analyze materials and processes on-site,” del Campo explains. “It can track the availability of steel, concrete, wood—automatically assessing material flows to ensure construction doesn’t get delayed due to shortages. If a critical material is running low, AI can notify the construction team in advance, preventing costly stoppages.”

The ultimate goal is to reduce errors, optimize workflows, and save money. “Mistakes in construction are incredibly expensive,” del Campo emphasizes. “AI can minimize those errors by catching them in real time—or even before they happen.”

The Future of AI in Architecture: A Balancing Act

As AI continues to reshape the AEC industry, architects and firms will need to find a balance between efficiency, creativity, and sustainability. Some will embrace AI as a tool to scale up and increase productivity, while others will differentiate themselves by emphasizing human-driven, bespoke design.

For del Campo, the key takeaway is this: “AI is not here to replace architects. It’s here to expand what we can do. Whether we use it to optimize sustainability, enhance collaboration, or streamline construction, AI’s greatest potential lies in how we choose to integrate it into our creative and professional processes.”

In an industry that has long been slow to adapt, architects who embrace strategic innovation—whether through AI or through positioning themselves as unique, high-touch design studios—will be the ones who thrive in the decades to come.

Overcoming Implementation Challenges: AI Adoption in the AEC Industry

As artificial intelligence continues to reshape architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC), firms face significant challenges in integrating AI into their workflows. These obstacles range from data collection and processing to organizational resistance and AI literacy.

“One of the biggest challenges is ensuring that the data being collected is ethical and unbiased,” explains Matias del Campo. “A lot of datasets today suffer from cultural, gender, and ethical biases. If companies want to implement AI responsibly, they need to build their own datasets instead of relying on pre-existing ones.”

This is easier said than done. Large architecture and construction firms may have decades’ worth of project data, but much of it is unstructured—spread across different formats, inconsistent, and difficult for AI models to process. “The key challenge is structuring this data, labeling it correctly, and making it usable for machine learning. That alone is a massive task,” del Campo says.

However, once companies overcome this hurdle, the benefits are substantial. “The most exciting thing about AI is when it provides insights that you didn’t expect. That’s when you really learn something new,” he emphasizes.

For AI adoption to be effective, firms must invest in infrastructure. “Large companies should have their own dedicated AI teams—at least one or two computer scientists working in-house to structure data, train models, and ensure AI is applied effectively to their practice,” he suggests.

“And, of course, they should hire my students—they know exactly what to do with AI in architecture.”

Bridging the AI Knowledge Gap: Training the Next Generation

A major roadblock to AI adoption in architecture is the industry’s resistance to change, particularly among senior leadership. “AI is disruptive, and many decision-makers in firms belong to an older generation that struggles with technological shifts,” del Campo notes. “Encouraging adoption means educating stakeholders and demonstrating the value AI brings.”

The key to fostering AI literacy starts in higher education. “The need for AI integration is being recognized across academia,” he says. “The interdisciplinary AI lab we started in Michigan—where computer science and architecture students collaborate—is now being replicated in other schools. Demand for AI-focused studios, workshops, and seminars is skyrocketing.”

Del Campo notes a shift in student attitudes toward AI. “At the beginning of every semester, my students’ first question is always, ‘Will I even have a job after graduation?’ There’s fear. But by the end of the semester, they realize that AI is not a replacement—it’s a tool. They understand that adapting to this technology is what will make them successful.”

The same mindset shift needs to happen in architecture firms. “Just like in nature, if a species doesn’t evolve, it goes extinct. The same applies to the profession. AI is not going away—firms that fail to adapt will struggle to survive.”

The Untapped Potential of AI in AEC: Breaking Free from Closed Systems

When asked about the most transformative yet underutilized aspect of AI in architecture, del Campo points to the shift from closed software systems to open AI ecosystems.

“Before the AI explosion, architecture relied on closed systems—whether it was BIM software, 3D modeling programs, or parametric design tools like Grasshopper,” he explains. “These were walled-off environments where you had to manually input every piece of external data.”

AI, however, represents the complete opposite. “It’s an open system, capable of integrating information from diverse sources—weather patterns, urban data, environmental factors, historical site conditions. This fundamentally changes design thinking.”

Traditionally, architects had to consciously choose what data to incorporate into a project. “If I wanted to analyze population density, I had to seek out that dataset and figure out how to integrate it into my design manually. Now, AI does that on steroids—it can instantly pull in vast amounts of information and process it in ways we never could before.”

This open-ended capability is what makes AI truly revolutionary. “Take something like ChatGPT—it’s trained on the entire corpus of human knowledge available on the internet. We

now have access to an infinite repository of possibilities, and if we use it cleverly, AI can reveal design solutions we never anticipated.”

This, del Campo believes, is the real potential of AI in architecture—not just automation, but discovery. “The most exciting moments happen when AI surprises us—when it presents solutions that challenge our assumptions. That’s where the learning happens.”

Revolutionizing AEC: A Future Beyond Modernism

Looking forward, del Campo sees AI as a catalyst for a new architectural paradigm—one that could finally move beyond modernism.

“The way AI processes information will inevitably change how our built environment looks,” he predicts. “It will introduce new design languages, new material efficiencies, and new ways of engaging with urban space.”

The implications extend beyond efficiency and sustainability—AI has the potential to reshape how we think about architecture itself. “If we use AI responsibly, we can make the built environment more sustainable, more socially responsive, and ultimately more intelligent. But it will require architects to step outside their comfort zones and embrace this transformation.”

For del Campo, AI isn’t just another tool—it’s the next evolution of architectural thinking. “The question isn’t whether AI will change the industry. It’s already happening. The real question is: will architects embrace it and lead this change, or will they resist it and fall behind?”

Either way, one thing is certain—the era of closed systems and rigid design methodologies is over. AI has ushered in a new age of openness, adaptability, and unprecedented creative potential. And for those willing to explore it, the future of architecture has never been more exciting.

The Deep House: A Dream Project in AI-Driven Architecture

When asked about his dream project, Matias del Campo resists the typical response. “Most people think of dream projects in terms of typology—an opera house, a museum, or something monumental. But for me, it’s more about the dimension of discovery rather than the scale of the project itself.”

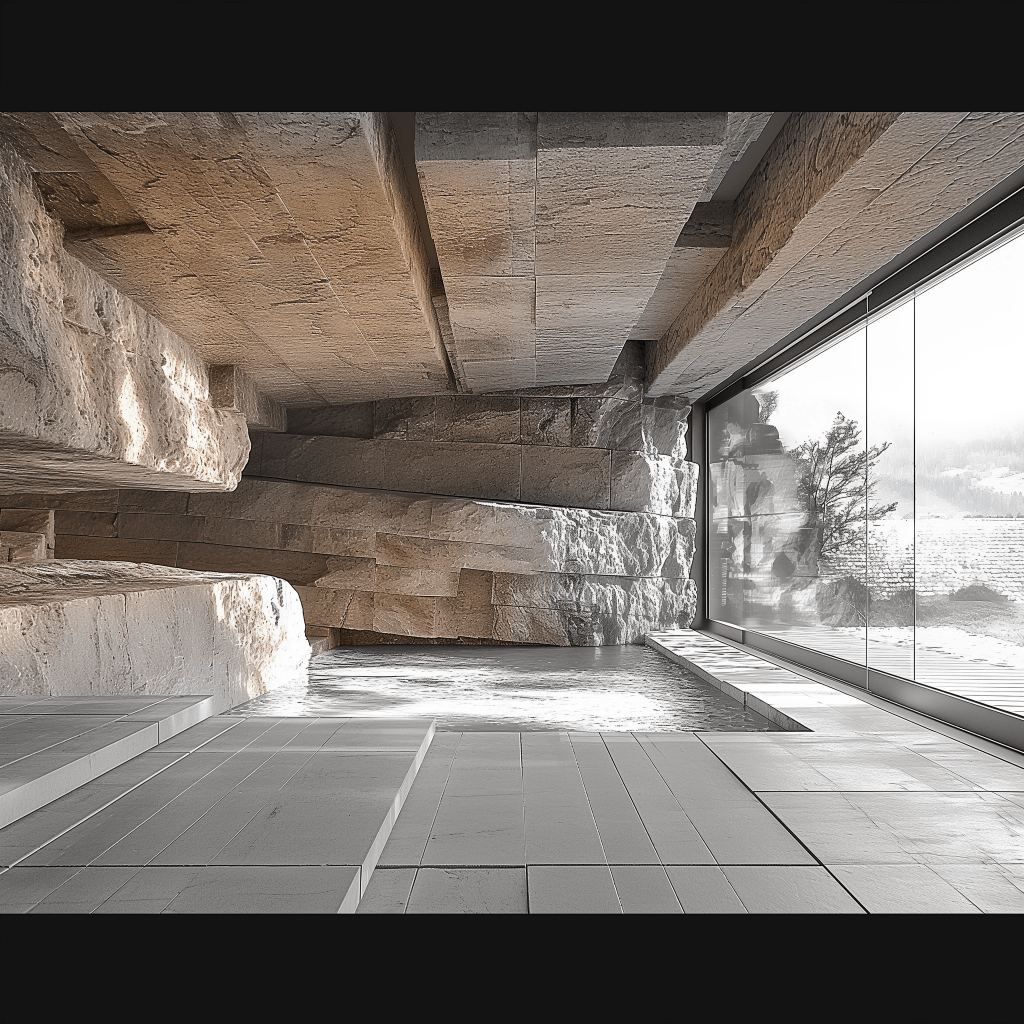

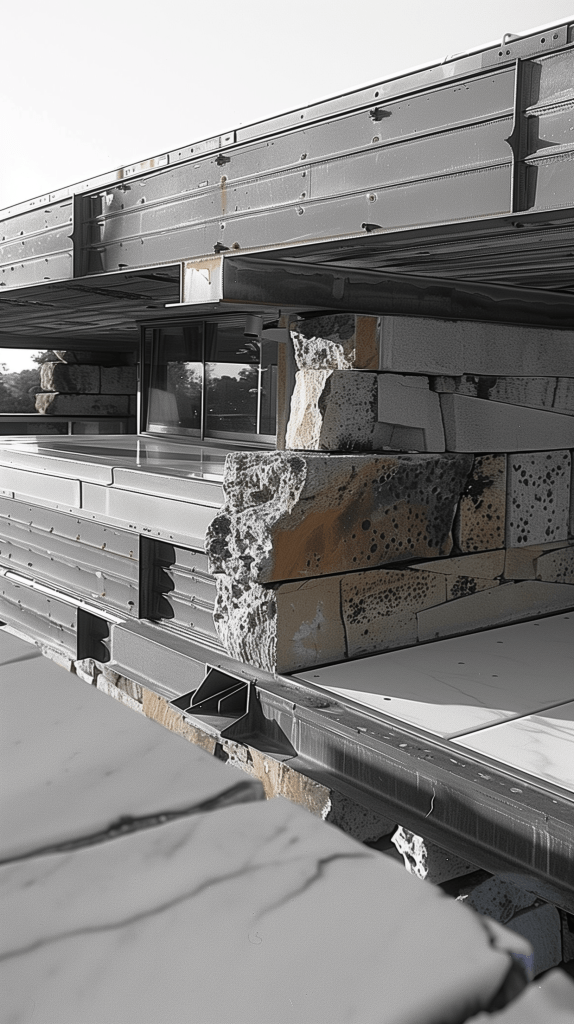

Deep House; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

Deep House; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

There is, however, one project that stands out—the Deep House, a weekend retreat in the mountains, designed entirely through a deep learning process. What makes it even more compelling is the identity of the client—a neuroscientist.

Deep House; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

Deep House; Image Courtesy: Mattias del Campo

“He came across our work and immediately connected with it,” del Campo explains. “He saw that we were engaging with the relationship between AI and neuroscience, and since AI itself is modeled on neural networks inspired by the human brain, he thought—‘These guys are working with ideas that come from my field. I want them to design my house.’”

But there was an unexpected twist. “The only condition he set was that the house had to be mid-century modern,” del Campo laughs. “And that’s where the fun began.”

Rather than designing a conventional mid-century modern house, del Campo and his team decided to train a neural network on a dataset of mid-century modern architecture. But instead of refining the model to perfection, they intentionally trained it poorly, introducing errors and randomness so that the AI would generate something that looked somewhat mid-century modern, yet completely unorthodox.

“The result was absolutely hilarious and beautiful at the same time,” he recalls. “You can clearly see mid-century modern elements—glass walls, flat roofs, long horizontal lines—but everything is slightly off. No mid-century modern architect would have designed it quite this way. It’s weird, elegant, and totally unique.”

For del Campo, this project exemplifies what makes AI so exciting—not just automation, but unexpected discovery. “AI introduced an element of strangeness and unpredictability, but at the same time, it still took human intuition to recognize its beauty and potential. That’s what makes this kind of collaboration between human intelligence and machine intelligence so compelling.”

The Human-AI Dialogue in Design

This balance between control and serendipity, between the familiar and the alien, is what makes AI-driven design so fascinating.

“It’s almost a joke,” del Campo reflects. “We trained the AI just badly enough that it barely understood the mid-century modern style, and what it produced was something completely unique. It takes intelligence to find humor in that, too.”

I agreed, noting how the project perfectly illustrates the dialogue between human and machine intelligence. “This is a beautiful example of what makes AI and human collaboration special. AI can generate possibilities, but it still takes human perception, intuition, and creativity to say, That’s it—that’s the one that works.” For del Campo, Deep House is just the beginning. “I would love to do more projects like this—where the discussion between AI and human creativity is visible, legible, and understandable to others. Projects that help people feel comfortable with AI, where they realize that AI isn’t taking over, but rather acting as a co-creator, allowing us to explore new realms of beauty, elegance, and meaning.”